How to keep produce safe from salmonella, other hazards

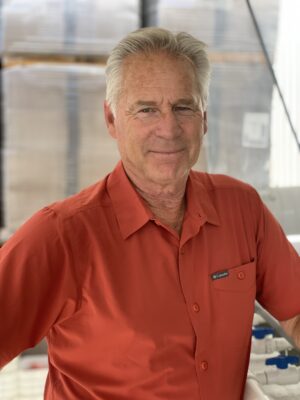

Trevor Suslow, an Extension research specialist at the University of California, Davis, is a key figure in fresh produce food safety, helping to define industry standards during his decades-long career.

As he moves to emeritus status with UC Davis, he talked to the Center for Produce Safety about produce safety’s evolution and evaluating related research.

Q: You’ve said you were pushed into produce safety. Why?

A: I worked for an ag biotech company after getting my Ph.D. in 1980. When we started rolling out products, buyers handed us their food safety specifications. Because I knew so many -ologies — agronomy, plant pathology, microbiology, etc. — management decided I was our food safety guy.

When I moved to Extension and research at UC Davis in 1995, I told them if they hired me, I would make food safety part of my program. I thought it would be a small part; it dominated what I did for the next 28 years, there and at Produce Marketing Association (now International Fresh Produce Association). So I say I walked through the food safety door and they locked it behind me.

Q: What does produce safety look like to you?

A: It’s being as broad and inclusive as you can, doing the best you can, to ensure the safety of the food you’re shipping to consumers. It’s understanding the hazards, characterizing the risks that are specific to you and drawing on available knowledge even if it’s not from your region, your commodity or your business model. It’s about the details, and the details of the details, integrated across the spectrum from production to harvest, packaging, processing, shipping, to retail.

The basic principles haven’t changed since we drafted the first industry-led Guide to Good Agricultural Practices for Produce Safety in 1995. But awareness and options to mitigate, control or avoid risks have evolved tremendously.

Q: What makes for good research?

A: I think successful research doesn’t just say “Look how bad this is” but rather, “Here’s the situation, and this is the science on best management to deal with it, and the best way to figure out if that’s going to work for you or needs a few tweaks.”

Overall, research that comes out of Center for Produce Safety has great directional value in showing what you should be doing, or what you should stop doing. CPS played a tremendous role at a critical time after the 2006 E. coli/spinach foodborne illness outbreak to consolidate industry and to bring government, public health agencies, academia and industry together to shape a different type of research mission — one that emphasized problem-solving, solution-driven, applied-answer research across the supply chain.

Q: Your research has been funded by CPS. What advice do you have about looking at research results?

A: Get in there and think like the pathogens. Look beyond the superficial stereotypes about their behavior. Learn how they adapt, how they survive and what makes them die.

The last couple of years, the research has been dominated by listeria, viruses and cyclospora — but don’t forget salmonella. There are 2,500-plus known types. It is probably the best of all pathogens at surviving and growing under stress — in the environment, on fresh produce and in packing and processing facilities. Once it has adapted to non-killing stresses, it can tolerate heat, freezing, pH extremes and sanitizers.

After outbreaks in 2020 and 2021, the dry bulb onion industry partnered with CPS on research to identify production practices that may contribute to salmonella contamination and how to reduce related food-safety risks. Oregon State University’s Joy Waite- Cusic and Texas A&M’s Vijay Joshi are thinking like pathogens — and also like crops. Waite-Cusic reported at CPS’ June Research Symposium that overhead irrigation resulted in more prevalent and persistent E. coli contamination (used as a surrogate for salmonella) of onion bulbs than drip irrigation.

Both projects are relevant to other produce and production conditions. Once completed, they should add to our understanding of how salmonella interacts with fresh produce and responds to environmental conditions. The research should also point to safer plant breeding options and lower-risk water application options, plus other crop management, harvest, curing, storage and processing practices.

Meanwhile, another recent CPS project identified a potential tool for bacterial pathogen control postharvest. University of Georgia’s Kevin Mis Solval found that low-cost infrared cameras added to common smartphones worked as well as higher-cost technology to measure produce surface and core temperatures across indoor environments.

Q: Is there a call to action here?

A: Leaders should empower and develop the skill base of their food safety professionals so they really understand how to dissect research and are able to figure out the “so what” of research — to watch for both the very positive side but also red flags. To help, CPS has created a really amazing, never-existed- before network of experts of all different kinds. You don’t have to figure this out on your own.

For more details about these and other CPS research projects, visit www. centerforproducesafety.org/funded- research-projects.php.